During a recent trip to London, we had the opportunity to sit down with executives from six UK-based banks, including teams from two High Street banks and four from what are commonly referred to as “Challenger banks”. In this note, we review our stance on U.K. banks, provide a brief breakdown of the market, and discuss our key takeaways from the trip.

We remain constructive on the U.K. banking sector, which includes ten “challenger” banks. For our Hamilton Capital Global Bank ETF (HBG), the U.K. banks (currently ~7% of the ETF’s portfolio) have been an important contributor to performance, particularly after going zero weight in the weeks before the Brexit referendum, and then re-building our positions after the sizeable correction following the vote (see our Insight, “HBG: Post-Brexit Portfolio Changes” for more details). For our more recently launched Hamilton Capital Global Financials Yield ETF (HFY), U.K. banks account for ~3% of the portfolio.

A Large and Varied Universe

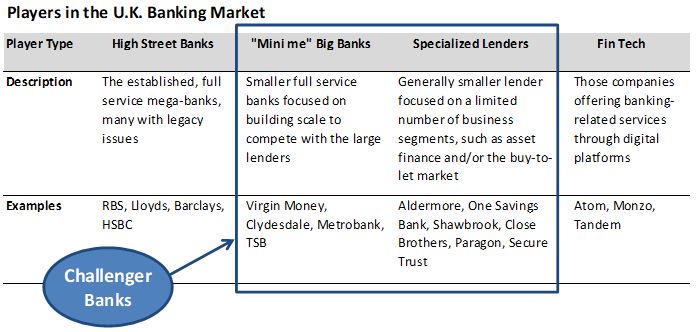

Most investors are familiar with the U.K.’s mega banks (e.g., HSBC, BARC, LLOY), often referred to as the “High Street” banks. Perhaps lesser known to Canadian investors are the so-called “Challenger” banks, now numbering in the double digits. The “Challenger” banner is an all-encompassing name used to denote the much smaller banking competitors looking to challenge the large established banks in one or more market segments. Arguably, their size relative to the High Street banks is the only facet these companies have in common (although they themselves even vary significantly in size). As one executive described it, the U.K. banking sector is effectively made of four different types of players:

Below are the key takeaways from our meetings:

- Consolidation – only if it makes sense for shareholders: For the smaller Challenger banks we met, executives were consistent with respect to balancing organic growth with inorganic growth (i.e., M&A). Most teams indicated the need to be “on their toes” but “pragmatic”, and that the “benchmark is high” for doing a deal. With the £27 bln asset Co-op bank in the news (as it seeks a buyer, or capital injection, to meet its capital requirements), it was the most noted possible target. However, all suggested Co-op was too complex and that bids for individual portfolios were most likely.

- Economic outlook varied: Although most banks seemed neutral-to-optimistic on the U.K. economy and market as a whole, one executive was more bearish that the others. Specifically, he noted his expectation for an economic slowdown over the next 18 months, and believed the government’s expectations are similar, suggesting that was part of the rationale for the Prime Minister’s decision to call an early election now.

- Little discussion/concerns around the upcoming U.K. election: At the time of our meetings, the more business-friendly Conservatives held a significant lead in the polls (48% to Labour’s 28%, according to the Guardian/ICM poll), so the June 8th election received little discussion. The foregone conclusion appeared to be that the Conservative would once again get a majority in the 650 seat House of Parliament. [Note, the Conservatives did not earn a majority, and subsequently entered into an agreement with the United Democratic Party (UDP), allowing them to form a government.]

- Biggest market segment concern? Unsecured personal: Several banks noted the growth in the U.K. unsecured personal loan market as a source of concern. Of those, most indicated they have either reduced or stopped writing new business, believing the loan category is being mispriced (rates offered dropped below 3% earlier this year for the first time ever). One executive expects the decision by the Prudential Regulation Authority (“PRA”) to review this market segment – as well as credit card and auto – could lead to market changes, possibly in the form of higher capital requirements.

- Mortgage market remains highly competitive, with spreads as low as one executive can ever recall: Peers mentioned certain High Street banks are being particularly aggressive in U.K. mortgages, which was attributed their very low cost of funds and higher liquidity. To compete and protect margins, Challengers are emphasizing service, including approval of a mortgage in as little as 30 minutes. One executive attributed its front and back office platform efficiency to a lack of legacy systems that typically slow the client experience at High Street banks, rather than weaker underwriting standards.

- Challengers banks at a capital disadvantage to their High Street Peers, but gap may narrow: The U.K. challenger banks do not meet the current requirements set out by the PRA to use the Internal Ratings-Based model (“IRB” – read: lower risk-weights) for calculating their capital requirements[1]. As a result, they are at a capital disadvantage to their High Street peers, since IRB models tend to results in lower capital requirements than those calculated using the Standard model. In certain business segments (e.g., residential mortgages), the difference is highly material (e.g., 35% vs 3% risk-weighting for loan-to-values < 50%). Consensus among the Challengers was that the regulator now recognizes the trapped capital within the standardized model, and that it is exploring ways to narrow the capital gap including: (1) reducing the capital add-ons for operational risk, (2) making the IRB model available for smaller banks. At this point, nothing is confirmed.

- IFRS 9 + IRB model for capital = Two birds with one stone for Challenger banks?: According to executives, IFRS 9[2] requires similar credit modeling for bad debt (i.e., non-performing loans) as that needed to get PRA approval for the use of the IRB models. One Challenger executive commented that the U.K. treasury and German authorities believe the smaller banks should not be subjected to IFRS 9, while another questioned whether it might be rolled-back entirely given the new global climate of regulatory reversal. In the meantime, the smaller banks are proceeding with making the investment to build the needed models, and may look to extend that work to get IRB model approval thereafter.

Notes

[1] Under the current Basel regulatory framework, there are two approaches to the calculation of a bank’s capital requirements: (1) the Standard approach (which employs the regulator’s set of risk weights by loan exposure type), and the Internal Ratings-based (“IRB”) approach (which allows the company to use its own internally-developed – and lower – risk weights). To be allowed to use the IRB approach, a bank must meet a slate of requirements, and be approved to its national regulator (for the U.K. banks, that is Prudential Regulatory Authority).

[2] IFRS 9, which applies to all banks except those in the U.S. (which still operate under U.S. GAAP), goes into effect January 1, 2018 and (amongst other things) changes the way companies recognize losses from an ‘incurred loss’ to ‘expected loss’ model. As a result of this change, banks are currently adjusting and/or building the necessary models to meet the standard requirements.