In our three-part series, Canadian Banks: How Worried Should You Be (about Rising Energy Losses, Low Reserves, and Recessionary Alberta)?, we have been reviewing the challenges facing the sector. In this Insight, we discuss another potential issue facing the Canadian banks: rising regulatory risk. With the sector near the bottom of global rankings for key capital and reserve ratios, we discuss the potential for policy makers to seek to close this difference.

- Part #1: Canadian Banks – Are Sectoral Allowances the Solution to Low Reserve Ratios?

- Part #2: Canadian Banks – How Worried Should You Be (about Rising Loan Losses, Low Reserve, and Recessionary Alberta)?

- Part #3: Canadian Banks – Are Falling Global Reserve/Capital Rankings Increasing Regulatory Risk?

Highlights

- Structural Changes in Global Banking Sector Reduce Canada’s Relative Ranking: Post credit crisis, much of the global banking sector underwent significant structural changes, including: building regulatory capital, improving capital quality, building reserves, simplifying business models, and improving liquidity. However, by avoiding the worst of the crisis, the Canadian banks did not need to restructure to the same degree as their global peers. Instead, a confluence of factors resulted in a relative decline in key reserves/capital ratios for the sector, including: (i) capital deployment/growth initiatives (which slowed capital growth), (ii) dividend growth (unlike many other countries, which forced banks to cut dividends to build capital), (iii) extremely good credit quality (which placed downward pressure on reserves, from highly pro-cyclical reserve accounting), and (iv) a much less aggressive domestic regulatory response to minimum capital levels. The cumulative effect is that the Canadian banks now rank near the bottom of global banks (source: SNL Financial, public banks only) on two critical ratios: common equity tier 1 ratio (“CET1”) and reserves-to-loans ratio (“reserve ratio”).

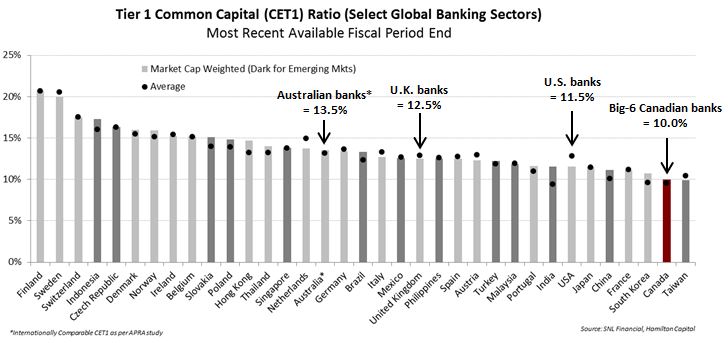

- Capital – On Regulator’s Preferred Ratio, CET1, Canada Ranks near Bottom: Despite a ~75% increase in the Big-6 Canadian banks’ tangible common equity – the highest quality capital – since 2011, the group’s CET1 ratio is just ~10%, well behind the average of global banks at ~13.7% (and U.S. banks at ~11.5%). We believe the majority of global regulators have adopted a de facto minimum CET1 ratio of 10% plus a cushion; of 35 countries we reviewed, half have CET1 ratios in excess of 13%.

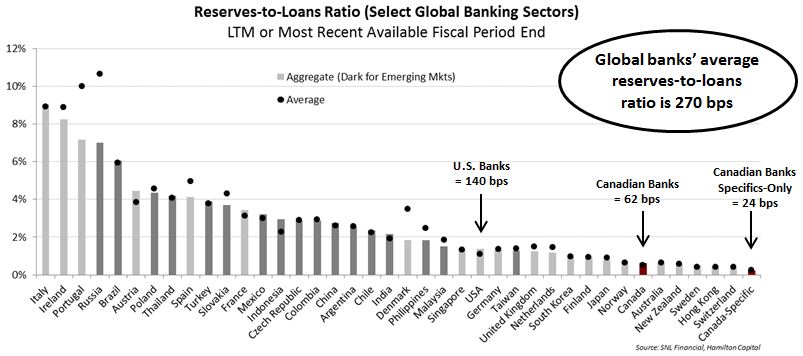

- Reserves – Canada’s Reserves-to-Loans Ratio Ranks near the Bottom of Global Peers; “Useable” Reserves Even Lower: As we discussed earlier in this series, Canadian bank reserves are not only low, but also of low quality. Constrained by highly pro-cyclical reserve accounting, the Big-6 Canadian banks’ reserve ratio is just 62 bps, well below the global banking sector average of 270 bps (U.S. banks at 140 bps). Compromising reserve quality is the fact that ~60% of reserves are in the form of “general” allowances, which we believe equity investors should consider to be ‘de facto’ unusable.

- Is Regulatory Risk Rising for the Canadian Banks? Hard to Conclude It Isn’t: With a relatively new head of OSFI, it is certainly possible that this change in oversight could result in an (potentially aggressive) effort to improve the banking sector’s global ranking in both reserves and capital. Should this occur – and it is not clear it will – it would be negative to shareholders, most obviously through downward pressure on ROEs (which have already fallen 500 bps in the past four years), but also through slowing earnings and dividend growth. We would note that over the past 8 years, global bank regulators have consistently imposed regulatory changes that were worse than the market expected, to the detriment of equity investors.

- For What It’s Worth… In Our View, Capital is Fine; Accounting Constraints Keeping Reserves Below What We Would Prefer: In our view, the Canadian banks have sufficient regulatory capital, while many global banks have too much capital, making it difficult for them to generate ROEs greater than their cost of capital. As for sufficiency of reserves, it is our view that the Canadian banks should seek to build up this key cushion, and that using sectoral allowances against deteriorating energy portfolios is a possible solution.

Note to Reader:

“Allowances” and “Reserves” are used interchangeably in this note. The former is the dominant term for Canadian banks, while the latter is more commonly used for U.S. banks. Collective allowances for loans not identified as impaired are referred to as “general allowances” or “collective general” in this note. Our global banking statistics are measured on a universe of banks that includes all publicly-traded banks defined and covered by SNL Financial LC with market capitalizations exceeding US$300 million, as of September 2015. As a result, some aggregate data for a particular country or region may not be the same as government reported data for its domestic sector.

Canadian Banks: Is Regulatory Risk Rising?

Post credit crisis, much of the global banking sector underwent significant structural changes. The scope and magnitude of these changes varied greatly by country, but invariably the emphasis was on building regulatory capital, improving the quality of capital, building reserves, simplifying business models, and improving liquidity.

By avoiding the worst of the credit crisis, the Canadian banks did not need to restructure to the same degree as their global peers, since the Canadian political/regulatory backlash was understandably less severe. Instead, a confluence of factors, including: (i) capital deployment/growth initiatives (which weighed on capital growth), (ii) dividend growth (unlike many other countries, which forced banks to cut dividends to build capital), (iii) extremely good credit quality trends (which placed downward pressure on reserves, from highly pro-cyclical reserve accounting), and (iv) a much less aggressive domestic regulatory response to minimum capital levels, resulted in the Canadian banks’ relative decline in two critical measures of balance sheet strength (compared to their global peers).

In this Insight, we discuss the Canadian banks’ relative ranking versus their global peers on two crucial measures of financial strength – capital and reserves – and whether those low relative rankings are increasing regulatory risk.

Capital: On Regulator’s Preferred Ratio, Common Equity Tier 1, Canadian Banks Rank near Bottom

Since the credit crisis, the Big-6 Canadian banks have increased their tangible common equity – the highest quality capital – by a very significant 75% since 2011. While improving the financial strength of the sector, this capital growth also contributed to a near 500 bps decline in ROEs (which would have been even larger were it not for the earnings tailwind from falling loan losses). Despite this significant increase in regulatory capital, with a sector aggregate ratio of ~10%, the Canadian banks have seen their global CET1 ratios ranking fall to close to last (the Canadian banks also rank near the bottom with respect to leverage ratios).

Meanwhile, over the past eight years, banks around the world have aggressively sought to raise their capital levels through: (i) equity raises, (ii) internal generation (i.e., earnings), (iii) dividend reductions (often temporary), and, in some instances, (iv) aggressive balance sheet shrinkage in the form of reducing “non-core” loans/assets.

And it has worked.

Most global banks have seen their capital ratios rise significantly as a result of these actions. As shown below, the global average[1] today is significantly higher than the Canadian banks, at ~13.7%. We believe the higher ratios around the globe owing at least in part to many countries having adopted a de facto minimum CET1 ratio of 10% plus a cushion. As a result, virtually all banks globally have common equity Tier 1 ratios well above 10%, with some countries significantly higher, including Sweden (~20%), Denmark (~16%), Norway (~16%) and Australia (~13.5%, “internationally comparable CET1 capital ratio” as per APRA study). The United Kingdom and United States are also materially higher, at 12.5% and 11.5%, respectively. To highlight how far behind the Canadian banks are, of the 35 countries listed below, half of the countries have CET1 ratios above 13%.

Reserves: Reserve Ratio near the Bottom of Global Peers, with “Useable” Reserves Even Lower

Another very important ratio used by global bank investors to assess balance sheet strength is reserves-to-loans (“reserve ratio”). As we discussed in Part #1: Canadian Banks – Are Sectoral Allowances the Solution to Low Reserve Levels?, Canadian bank reserves are not only low, but of low quality. In fact, the Big-6 Canadian banks’ reserve ratio is just 62 bps, versus the global banking sector average of 270 bps, the U.S. banks at 140 bps, and the Canadian banks’ own 15 year average of 100 bps.

Of great relevance to equity investors is the fact that 60% of Big-6 Canadian bank reserves are in the form of “collective general allowances”, which are generally not allowed to be drawn down in any significant way against portfolio impairments. Therefore, in our view, equity investors should consider them to be “unusable”. As we noted in Part #2 of this series, we focus, as do most international investors, on reserve ratios versus coverage ratios (allowances to gross impaired loans), as the utility of the latter to assess reserve adequacy declines significantly during periods where gross impaired loans are changing materially.

Is Regulatory Risk Rising for the Canadian Banks as a Result of Globally Low Reserves/Capital Levels?

As mentioned, the global banking sector has undergone significant structural changes since the credit crisis, as global regulators sought to diminish the risk of their banking systems, and ostensibly avoid, or reduce the risk of another crisis. During this period, the Canadian banks raised capital levels, but also shrewdly took advantage of their relative strength by allocating capital in ways that were clearly beneficial to the sector/system[2], and saw reserve ratios decline owing to extremely good asset quality trends.

Nonetheless, the fact that the Canadian banks are at or near the bottom of global capital/reserve rankings today is significant and at least implies regulatory risk is rising. And there is precedent. For example, a government-mandated inquiry in Australia suggested that the country’s regulatory body, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), “set capital standards … to be unquestionably strong” and that “[Australian banks] should have capital ratios that position them in the top quartile of internationally-active banks”. Although the APRA has not increased capital requirements for this recommendation, it did suggest “the top quartile positioning as a useful ‘sense check’”[3]. We cite this only to highlight that a country/banking system very similar to Canada is reviewing whether to include a relative ranking when assessing appropriate capital levels.

With a (relatively) new head of OSFI, it is possible that the change in oversight could result in an (potentially aggressive) effort to improve the sector’s global ranking; undoubtedly, this would be negative to shareholders, most obviously in the form of lower ROEs, which have already fallen 500 bps in the past four years, but also through slowing earnings and dividend growth. It is worth noting that, over the past eight years, global bank regulators have consistently implemented rules and imposed regulatory changes that were worse than the market expected, with the stated objective of reducing the risk(s) of future bailouts/financial crises. Policy makers have regularly “moved the bar”, even after communicating their intentions to the market and overwhelmingly to the detriment of equity investors.

So, what do we think?

For what it’s worth, in our view, the Canadian banks have sufficient regulatory capital, and that large parts of the global banking sector actually have too much, as evidenced by the many global banks unable to generate returns on equity (ROEs) in excess of their cost of capital. Until the global banking sector reprices its products higher – a process that could take years – these low returns will weigh on share price appreciation of those banks. While the dramatic increase in capitalization of the global banking sector is almost always described by policy makers/financial media as unambiguously positive, requiring banks to materially raise their capital levels invariably weighs on loan growth. This relationship is inherently deflationary and has likely been a contributing factor to the weak GDP recoveries of many economies during this most recent downturn.

On reserves, ratios are lower than what we would prefer, given looming direct/indirect losses stemming from the decline in oil prices. However, constraints imposed on the sector by highly pro-cyclical reserve accounting have made it difficult for the Canadian banks to set aside funds for expected losses. As we noted in Part #2, exceptionally low “usable” reserve ratios likely mean looming credit deterioration (most likely in the energy and Alberta uninsured consumer portfolios) will go through the income statement (possibly much larger than being contemplated by analysts), increasing the risk of earnings downgrades. We fully expect the sector to seek to build up from these extremely low levels, possibly through the use of sectoral allowances (as explained in Part #1 of this series).

Notwithstanding our views, we think the fact the Canadian banks are basically at the bottom of the global rankings in two of the most important ratios in banking likely means that regulatory risk is rising.

Notes

[1] Average across the 35 global banking sectors shown in the chart. The Canadian banks are shown on a market-cap weighted basis, using “all-in”/“fully-loaded”/“fully phased-in” capital requirements. The global banks are shown on a market-cap weighted basis, using “transitional” or “all-in”/“fully-loaded”/“fully phased-in” capital requirements, and include the largest publicly-traded banks in each country. For the global banks, data presented is “fully-loaded” or “transitional”, depending on availability by country / bank, with “fully-loaded” given preference if both sets of ratios are available, as it is the more conservative measure. The “all-in”/“fully-loaded”/“fully phased-in” basis of regulatory reporting includes all of the regulatory adjustments that will be required by 2019. Per Scotiabank, “Transitional requirements result in a 5 year phase-in of new deductions and additional capital components to common equity. Non-qualifying capital instruments are being phased-out over 10 years and the capital conservation buffer is being phased-in over 4 years.”

[2] Examples include, but are not limited to, the acquisitions of Marshall & Ilsley by BMO, the large upgrade in RBC Capital Markets, and Scotia’s acquisition of ING Canada. The damaged status of global banks also likely made it easier for RBC to acquire City National, a highly respected California bank with an excellent private banking business.

[3] Source: APRA Website (www.apra.gov.au/mediareleases/pages/15_18.aspx)